Abstract

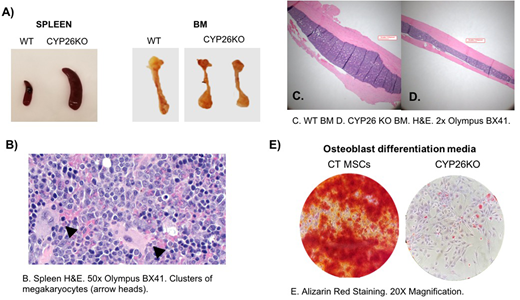

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in a complex microenvironment that enforces the balance between self-renewal and differentiation. The exact physiologic mechanisms by which the niche controls HSC fate remain elusive. Retinoic acid (RA) is a powerful morphogen that controls stem cell behavior across a variety of systems. In bone marrow (BM), mesenchymal stroma cells (MSCs) express cytochrome P450 (CYP)26 enzymes and can inactivate endogenous and pharmacological retinoids (Ghiaur G et al PNAS 2013, Su M et al. PlosOne 2015, Alonso S et al. 2016). Stromal CYP26 activity is required to maintain human HSCs ex vivo (Ghiaur G et al PNAS 2013). Here we set to study the role of CYP26 in HSC homeostasis in vivo. For this, we induced CYP26 knockout via injection of Tamoxifen in ROSA26CreERT CYP26A1loxP/loxPCYP26B1loxP/loxPmice (CYP26KO) and ROSA26CreERT wildtype mice (CTR). After 5 daily tamoxifen injections, the knockout was confirmed at DNA and RNA level in multiple tissues of CYP26KO mice. Within 4 weeks, CYP26KO mice showed profound leukocytosis (5.97 ±0.37 vs. 21.12 ±3.81 k/mm3, n=4, p<0.01 CTR vs. CYP26KO) with neutrophilia and monocytosis compared to CTR mice. By 6 weeks, they experience profound weight loss, became moribund and had to be sacrificed. At that time, they had massive splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy as well as brittle/pale bones compared to CTR (Figure A). Histological analysis revealed presence of extramedullary hematopoiesis with a predominantly myeloid infiltrate in the spleen (confirmed by flow cytometry analysis) and lymph nodes but also multiple clusters megakaryocytes (Figure B). The mice also displayed decreased BM cellularity (11.25 ±1.01 vs. 5.62 ±0.36 x106/femur, n=5, p<0.01, CTR vs. CYP26KO), increased frequency of CFU-C (44.33 ±3.72 vs. 69.83 ±8.10 CFU/25000 BM mononuclear cells (MNCs), n=10, p=0.02, CTR vs. CYP26KO) with a myeloid bias (26.76±3.89 vs. 44.57 ±3.21 %CFU-GM/G/M, n=10, p<0.01, CTR vs. CYP26KO). When cellularity was taken into account, total CFU-C per femur was comparable between the two groups. The mice also had increased frequency of LSK cells in the BM (0.26 ±0.12 vs 0.73 ±0.18 % LSK of MNCs, n=2, CTR vs. CYP26KO) and an increased frequency of circulating CFU-C in the peripheral blood (37 ±4.04 vs. 179.5 ±43.06 per 200 ml of blood, n=4, p=0.01, CTR vs. CYP26KO). On histological analysis, the BM is dominated by a myeloid infiltrate and shows a striking decrease in radial bone diameter (Figure C,D). MSCs derived from CYP26KO mice have lower levels of CXCL12 and SCF and have impaired osteoblast differentiation potential compared to MSCs derived from control mice (Figure E). These findings were confirmed with ex vivo generated CYP26KO MSCs via retroviral mediated Cre recombination of CYP26A1loxP/loxPCYP26B1loxP/loxPstroma cells. More so, preliminary studies suggest that the hematopoietic phenotype observed depends on cell extrinsic presence of CYP26 activity as transplantation of CYP26A1loxP/loxPCYP26B1loxP/loxP BM cells into wildtype BoyJ recipients did not reproduce the phenotype upon injection with Tamoxifen of the recipient mice in spite of 100% donor derived hematopoiesis. Alternatively, transplant of wildtype cells into CYP26A1loxP/loxPCYP26B1loxP/loxPrecipients, did reproduce the phenotype after injection of Tamoxifen. In conclusion, we show here that dysregulated RA homeostasis in the BM impairs MSCs function and result in egress of hematopoiesis to extramedullary sites. These results come to complement data from RARγKO (Walkley CR et al Cell 2007) and SMRTmRIDmice models (Hong S-H et al PNAS 2013) and suggest a pivotal role of RA signaling in pathogenesis of myeloproliferative neoplasm and myelofibrosis. To what extent these findings correlate with human primary myelofibrosis is currently under investigation.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.